I’m someone who likes to talk about politics at home and criticize it in any way I find appropriate. By family often asks me politely (or not very) to shut up, people unfollow me on Twitter for my overactive behaviour. By nieces and nephews block me in messengers for sending them articles to read, and my girlfriend always stops me from getting into arguments. People are always like that until their personal needs or interests are touched.

Of course, I wasn’t surprised when, after Donald Trump has won the US elections, I’ve read tons of workplace advisers’ articles mentioning that people should avoid discussing it at work. One of the articles in Harvard Business Review suggests the following thing. If you feel like you can’t keep calm while discussing the matter, it’s better to leave the conversation rather than continue the dispute.

On the website payscale.com there is a piece bearing the headline: “Pre-election Day Reminder: Talking About Politics at Work is a Bad idea”. And a survey by the Society for Human Resources conducted in 2012 found that a quarter of employers in the US had specific policies on political activities, which can include restrictions on political talk in the office.

Even if you loathe someone’s political point of view it is hard to truly despise them if you have seen them struggle with a vending machine earlier that day

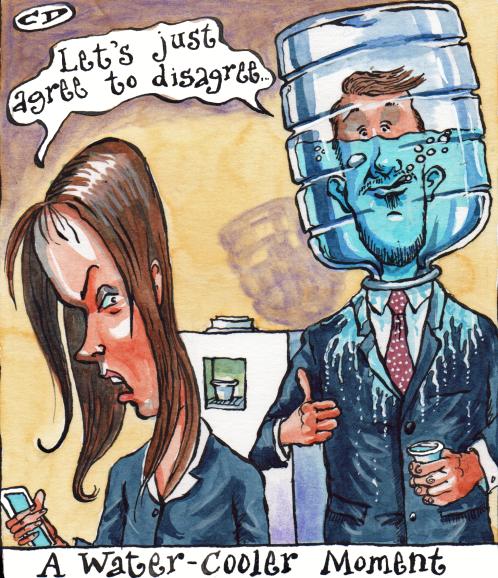

I can’t say I know of any British companies with similar policies but I understand the reasoning behind them. Political debate has, in the 21st century, ceased to be civilised: whatever the result, a good chunk of America was going to wake up on Thursday feeling that their country was no longer home; extremism in politics means people on all sides feel their identities are being attacked on a fundamental level; and my colleague Janice Turner was right to point out at the weekend that since Brexit the “poisonous discourse of social media has seeped up through the water table into real life”, with people not even being able to “agree on how we disagree”.

Tensions are high everywhere, including the workplace. A friend who works in marketing tells me that her office recently had to ban discussion of Brexit because it “was getting too heated”. The FT reported in August that PwC was advising four London companies whose pro-Brexit staff had complained of being ostracised as a result of angry social media posts and office discussion about the vote. Meanwhile, the Society for Human Resource Management reported last month that tensions in American offices were up 52 per cent compared with previous elections.

At the risk of sounding like certain Brexiteers, I disagree with the so-called experts on the subject. If anything, discussions about politics need to be encouraged in the workplace. Why? Well first, corporations have for decades been talking about corporate social responsibility, equality and the importance of environmental responsibilities and the least we deserve as employees, after years of sanctimonious lectures, is to know whether these ideals are going to be abandoned with the arrival of right-wing politics.

Second, politics is already present in the workplace as a result of social networking: one can tell quite simply from the things colleagues “like” on Facebook, Twitter and Linkedin where they stand politically, and it is impossible to forget once you do know. Third, and most importantly, the workplace is perhaps the only place where civilised political discussion remains possible.

The social psychologists Jonathan Haidt, at the Stern School of Business, New York University, and Ravi Iyer, at the website Ranker, were right when they argued in The Wall Street Journal this week that “stunning levels of incivility, including racist and sexist slurs and threats of violence” were becoming common because “ever more of our social life is spent online, in virtual communities or networks that are politically homogeneous”, and that when you only ever “rub up against the other side online” the relative anonymity has a coarsening effect.

Not only is such anonymity not possible in most offices but, because of rules and human resources departments, we are also obliged to behave well towards others at work. Indeed most of us behave better in the workplace than we do almost anywhere else, up to and including our own homes. Or at least, we are obliged for the sake of career development to listen more, shout and swear less, and do not generally conclude arguments with rape and death threats. Which is precisely what political discourse requires. Or, as Haidt and Iyer say, it is important to “spend time together, and let proximity . . . strengthen ties. Familiarity does not breed contempt. Research shows that as things or people become familiar we like them more.”

How would this work in practice? Well, I don’t think much of the painfully awkward wording suggested by some experts, with one recommending that, instead of exclaiming things such as “You’re an isolationist idiot”, you should tell colleagues: “I hear your passion about keeping employment low and keeping jobs in the US.” Or another who advises that we respond to someone with whom we disagree using the words: “I sincerely value people who are enthusiastic and involved in the democratic process, no matter what party or political group they are part of.” But actually The Times is not a bad example.

We are a pretty broad church and, on the whole, get on quite well. Because even if you loathe someone’s political point of view it is hard to truly despise them if you have seen them struggle with a vending machine earlier that day, or if they write something else on a non-political matter that made you laugh, or you see their kids waiting for them in the foyer after work. Not that it is perfect. There are arguments, and some of us truly cannot stand one another, but it kind of works and it seems to me that the civilising effect of the workplace is one of the few hopes we have at the moment.

- Navigating Career Opportunities in the Innovative World of Non-Gamstop Casinos - January 22, 2024

- Exploring Unconventional Career Paths: The Rise of Remote Casino Professionals - January 22, 2024

- What Qualifications Do I Need to be an Electrician? - November 22, 2023